By Dr Wendy Dossett

Beliefs and emotions are commonly accepted features of spirituality, but spirituality also includes ‘disciplines’ and ‘practices’. While ‘professional’ language and the ‘spiritual’ practices of 12-Step recovery may be framed differently, they are not substantively different discourses.

In setting the ‘spiritual programme’ of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) alongside the evidence for AA’s mechanisms of behaviour change (MOBC), Dr John Kelly highlights the problematic relationship between secular professional treatment and 12-Step mutual aid [in terms of language and ideas]. Research undertaken in the United Kingdom demonstrates that its apparently ‘religious’ nature is a significant factor in skepticism about 12-Step mutual aid among professionals and their clients. As a result, the number of people availing themselves of what Dr Kelly aptly describes as ‘the closest thing… to a free lunch in public health’ is reduced.

In that context, the effort to understand what, if anything, spirituality might add to AA’s ‘mechanisms of behaviour change’ is important. The MOBC for which there is the best evidence is the facilitation of adaptive social network changes (‘changing your playmates’). Kelly identifies spirituality as the ‘scaffold’ which mobilizes or catalyzes this and other social, cognitive, and affective mechanisms. This, he argues, is effective in part because of its inherent pragmatism: the ‘whatever works’ approach in relation to the God concept, and the development of positive emotions.

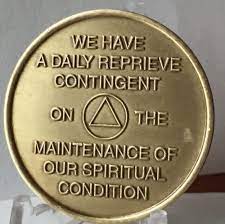

Spirituality is, however, as much to do with disciplines and practices as with beliefs, attitudes, or emotions. Key to AA’s approach is a ‘daily programme’. This is embedded in the Steps themselves. The daily inventory and renewal of a commitment to abstinence and altruism is explicitly religious or spiritual for a minority, and may involve prayer or meditation for some. However, for most participants interviewed in the Higher Power Project, a UK qualitative study of the spirituality of people in 12-Step recovery, the daily programme is simple common sense.

AA presents addiction to alcohol as symptomatic of a deeper illness. On this understanding, someone aspiring to long-term abstinence must address underlying emotional difficulties. Fear, resentment, guilt and shame are characterized as drivers of addictive behaviour to be countered by identifying their effects through moral inventory in Steps Four and Ten, by an ongoing commitment to change in Steps Six and Seven, and by making amends without further damage in Step Nine.

While the language in which this is expressed in AA texts and meetings seems religious, even pious or moralistic, it can be re-framed entirely in psychological and affective terms. Challenges are faced by people whose addictive behaviour has led to the dissolution of their recovery capital, in terms of financial security, positive family and community relationships, self-esteem and self-efficacy. These challenges diminish when responsibility is assumed and resulting issues are addressed practically. Without an ongoing effort to do this it is easy to see why abstinence is so difficult to maintain. External problems, combined with lack of personal resources to face them, sabotage efforts towards recovery. Thus, the (spiritual) discipline of working the Steps in the context of a daily programme provides the mechanism for recovery. It may help to identify this discipline as one of the MOBCs—additional to beliefs and emotions.

The findings of the Higher Power Project entirely support Kelly’s answer ‘yes’ to the question of whether AA is religious, spiritual or neither (it’s dependent upon how it’s related to). However, the root of the troubled interface between professional treatment and 12-Step mutual aid also lies in the failure of professional treatment to appreciate the relationship between.. ‘experience near’ and ‘experience distant’ concepts. 12-Steppers describe character defects, fellowship, spirituality; and professionals describe recovery capital deficits, adaptive social networks, and self-efficacy. They are not substantively different concepts; they are merely expressed differently. Dr John Kelly implies that the professional conceptual framework is ‘terrestrial’ (clinical, secular, cognitive), in contrast with the spiritual language of AA. Perhaps, one framework is not superior to the other.

The above article is adapted and was originally published in the journal ‘Addiction’ (Society for the Study of Addiction, 2017), and was written by Dr Wendy Dossett, who is based at the University of Chester.